Emptying the Sea

Senegambian Coast

Emptying The Sea is an investigation into the social and environmental impacts of Fishmeal & Fish Oil (FMFO) along The Gambian coast. The investigation was led by LIMINAL in the context of the ERC funded Hostile Environments project, and conducted in partnership with Malagen Investigative Journalism and The Gunjur Conservationists and Eco Tourism Association (CETAG). The investigation focused on the waters off the coast of West Africa where industrial and extractive processes are driving environmental collapse and widespread displacement. Along the West African coast fish has for centuries been a staple food source for artisanal fishers and coastal communities, as well as a central element of their economy and culture. However, this ecosystem is under threat from the growing influence of predominantly Chinese-owned Fishmeal and Fish Oil (FMFO) factories which are appropriating vast amounts of pelagic fish stock, particularly in The Gambia. In lieu of government accountability and amidst increasing corruption our investigation sought to document and denounce the damaging socio-economic and environmental impacts of FMFO production in The Gambia, highlighting the ways in which these extractive practices push many to seek livelihoods elsewhere1.

Extractions

Evidencing the social and environmental footprint of fishmeal fish oil production along The Gambian coast.

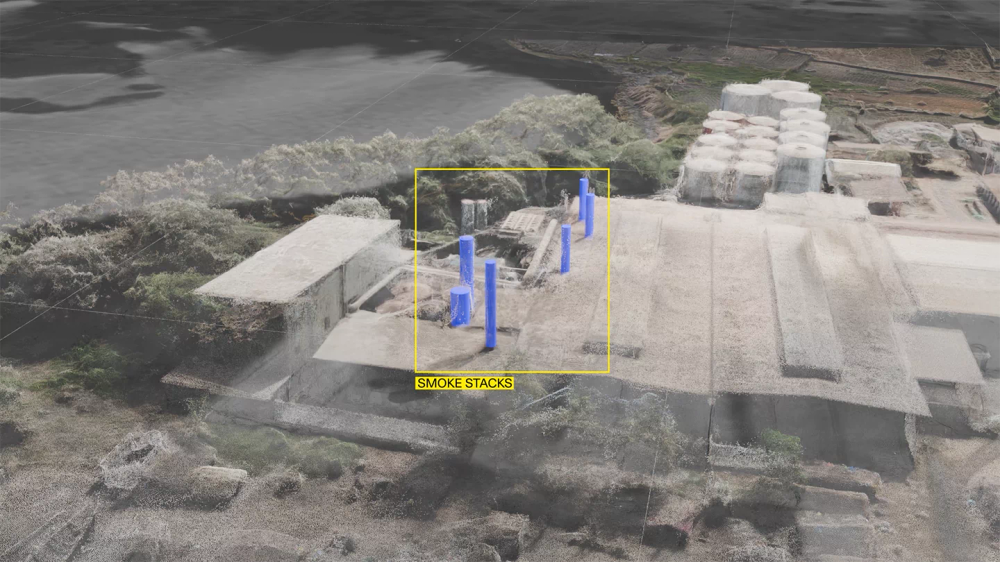

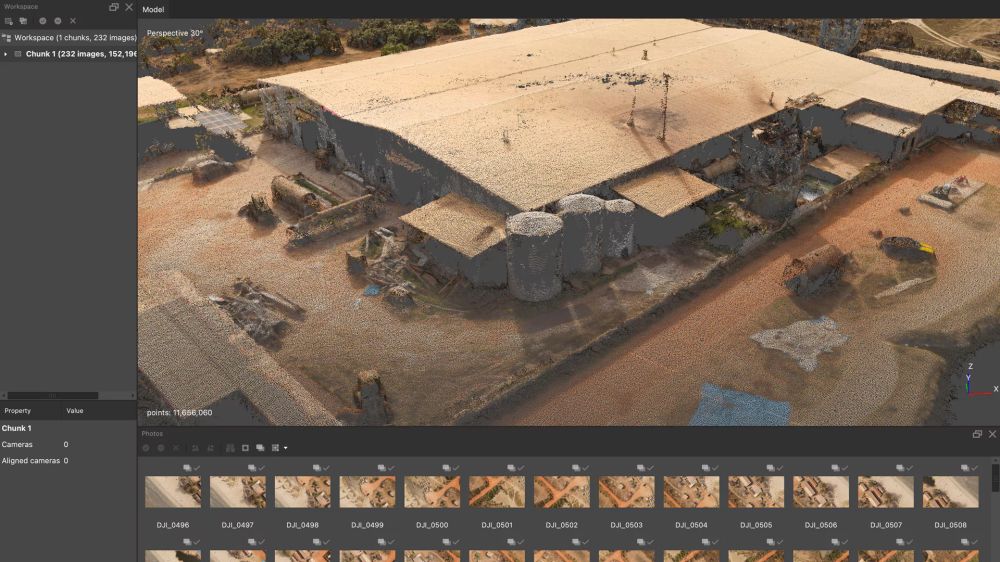

The investigation focused on key sites of acute environmental disruption along the Gambian shoreline, each home to foreign funded FMFO factories which are transforming the social and environmental dynamics of the surrounding fishing communities. The investigation utilised 3D forms of analysis and spatial reconstruction to document instances of environmental degradation2 and amplify testimonies of affected communities. Whilst creating, for the first time, a geo-spatial database of environmental damage caused by The Gambia’s largest FMFO factory; the Golden Lead factory at Gunjur beach.

Through open-source research methods and community outreach practices the investigation further documented the rise in corruption and evasive cooperate patterns surrounding The Gambia’s FMFO factories. With the emergence of the Gambian coast as a global FMFO market attracting vast amounts of largely Chinese capital, through the establishment of industrial FMFO factories at Gunjur, Sanyang and Kartong. Our investigation documented not only the social cost associated with increasing and widespread corruption but the modes of resistance3 being implemented by local communities in the face of little political representation at a local, national and international level.

During our investigation the development of methodologies in geo-spatial analysis and techniques in remote sensing aimed to widen the space of accountability for governmental organisations. And further, help equip local communities with the tools and resources to denounce the socially and environmentally unsustainable practices unfolding around them. Methodologies such as the monitoring of artisanal fishing activities with PlanetScope imagery using open-source software QGIS will be made publicly available via our website alongside our preliminary findings.

Displacements

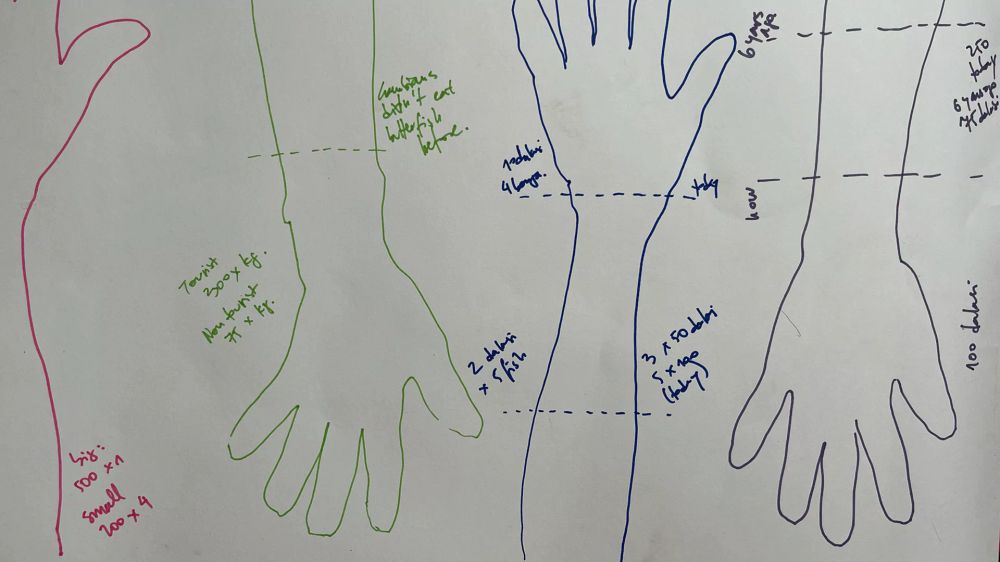

Workshops on the social effects of FMFO production led by Clara Dublanc at the Tanji Village Museum, Sanyang Community Library and the Gunjur primary school

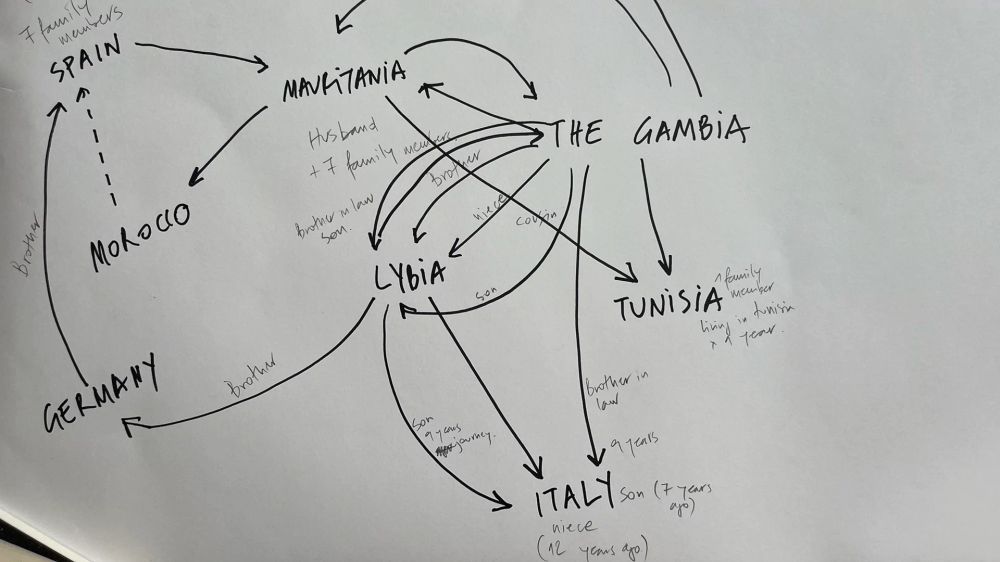

In addition to documenting the environmental and social impacts of FMFO production in The Gambia the investigation evidences how proteins subtracted from coastal communities in Western Africa are feeding Europe’s growing aquaculture and agriculture industries, whilst displacing an unknown number of coastal communities. These intensive EU farming practices dependant on FMFO products from Western Africa do not only constitute an environmental threat in themselves, they further food insecurities4, with food products utilising Western African FMFO often exported back to the region as cheaper, less nutritious, sources of protein. Ultimately, driving forced displacement5 throughout the West African coast as communities struggle to subsist off local proteins and fishing related industries.

Whilst West Africa’s FMFO industry is predominantly funded through Chinese capital, Changing Markets foundation have highlighted over 14 European companies6 importing FMFO products from the region in 2019. In the same year, these companies and others imported over 120,000 tons of fishmeal and 45,000 tons of fish oil from The Gambia, Senegal, and Mauritania to Europe. Imports which fuel social and environmental degradation along The Gambian coast, as highlighted in the testimony of a project participant and women fish vendor who tragically lost her life since providing this account of the hardships bought about by FMFO production.

“This factory [Nessim Factory Sayang], frankly, is not good for us. Because, if we look at it, like right now, sometimes we go there and we don’t find fish. The fish they catch is not always good fish. They catch any fish their hands come across. And the fish we use are carefully selected, some types of fish we do not need. But the kind of fish they catch is usually mixed. Sometimes even for us to get fish it becomes difficult. Recently we have seen them implement new regulations, but the fishermen normally go straight to the factory, even if they have good fish. If they have good fish, they prefer to give it to the factory rather than give it to us. At least now we have seen a new administration, and our complains have reached them. And the fishermen were told that if they arrive with fish, the citizens who are there should be get it first before it goes to the factory. Right now, we say that its it good for us because we can get our food but, in the future, it is not good for us. Because of what we breath when we go there, what the machines spit out. Truly it is not good for our health. If the factory starts, even if you are home, you can smell the stinky odour.”

“Secondly, it is this factory that makes fish expensive here, because if they are fishing, they fish out everything. These ‘Fila turnes’ that go there usually carry along all the baby fish that is not useful for us. The fish that should reproduce for tomorrow all goes that way. The factory makes fish expensive in The Gambia, we think that it helps us but if you come to look at it closely, this factory does not help us, it does not help us because it makes fish expensive here. It makes it difficult in The Gambia here.”

Future Trajectories

Europe's (and in particular Spain’s) role in resource extraction and FMFO production along the West African coast happens against a backdrop of border externalisation7, which seek to immobilise the very peoples displaced8 by extractive policies and practices. Future investigations alongside Italian investigative journalism outlet IrpiMedia and Spanish NGO porCausa will trace the involvement of Spain and Italy in border externalisation, the criminalisation of migrants and resource extraction throughout the region. In turn, highlighting the duality of Europe’s role in further bilateral fishing agreements9 which ultimately drive forms of migrations they latter attempt to stop.

These interlinking patterns of migration, criminalisation and resource extraction reveal a complex network of mobility between both ECOWAS nations and their European neighbors. Unfolding across a time in which certain forms of mobility have been increasingly criminalized by European actors in the region: negotiating the establishment of outposts by the Spanish Guardia Civil as well Frontex10, the European border and coast guard agency; signing deportation agreements with West African states; and criminalizing those coming from West African coastal communities as dangerous smugglers when caught (allegedly) driving migrant boats to Spain or Italy, weaponising their in-depth knowledge of the sea against them.

Future research efforts aim to document these ongoing practices of faced by migrants on European Soil. Throughout prisons in The Canary Islands and Sicily dozens of both West and North African fisherfolk await trial, accused of human trafficking after navigating repurposed fishing vessels to European shores. Common throughout their stories is their displacement from their coastal homes in the face of dwindling fish stocks, and the growing demands of Europe's consumer markets. Future research in this space aims to follow their stories, and the role of Spanish and Italian actors in both their incarceration and the pillage of their coastal waters.

Team & funding

Core Team

Extended Team

Collaborators

Funding

Resources

Reports

Amnesty International, "The Human Cost of Overfishing in The Gambia; how the overuse of fisheries resources in sanding threatens human rights." Amnesty International LTD, 2023. ↗

Changing Markets Foundation, “Feeding a Monster; how European aquaculture and animal industries are stealing food from West African communities." Changing Markets LTD, 2021. ↗

Changing Markets Foundation, “Fishing for Catastrophe.” Changing Markets LTD, 2019. ↗

Greenpeace, “A Waste of Fish; food security under threat from the fishmeal and fish oil industry in West Africa.” Greenpeace International, 2019. ↗