Hostile Environments

Agadez Region, Central Mediterranean, London, Senegambian Coast

Across the world, state borders are being increasingly militarised and migrants funnelled into more and more hazardous terrains such as oceans, mountain ranges and deserts. In the last few years alone, several thousands have died while crossing these hostile environments, whose material geographies are harnessed as crucial tools of border control. At the same time, across and beyond urban geographies in the Global North, a generalised atmosphere of hostility has led to shrinking forms of social protection for those classified as outsiders, with legislation passed to deny migrants access to work, housing, services and education. This project sets out to reframe the notion of “hostile environment”, first introduced in the migration debate in the UK in 2012 to refer to such anti-migrant laws, as a conceptual and analytical lens to capture these distant but interconnected processes, whereby “natural” and civic spaces alike have been weaponised by extractive processes, surveillance technologies, border control practices and bureaucratic protocols. In all these cases, the border should be understood as a pervasive environment that subtracts life-sustaining resources (from water and food to rescue and healthcare provisions) and exposes migrants to harsh socio-natural conditions (not only extreme heat or cold, or chronic food and sleep deprivation, but also the lack of access to any social support). Here the environment stops being simply a site of border control, and rather becomes one of its modes of operation.

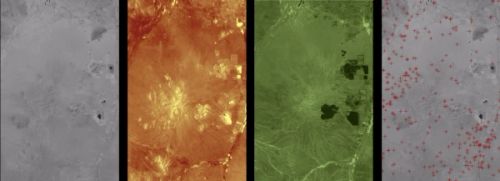

Going beyond the catastrophist and security-oriented perspectives that dominate these debates, the Hostile Environments project (HEMIG) will develop arts-based strategies of spatial and visual analysis to capture the entangled nature of border and environmental violence and its harmful effects. A multidisciplinary team will focus on three border environments located along a typical migrant trajectory linking Sub-Saharan Africa to northern Europe.

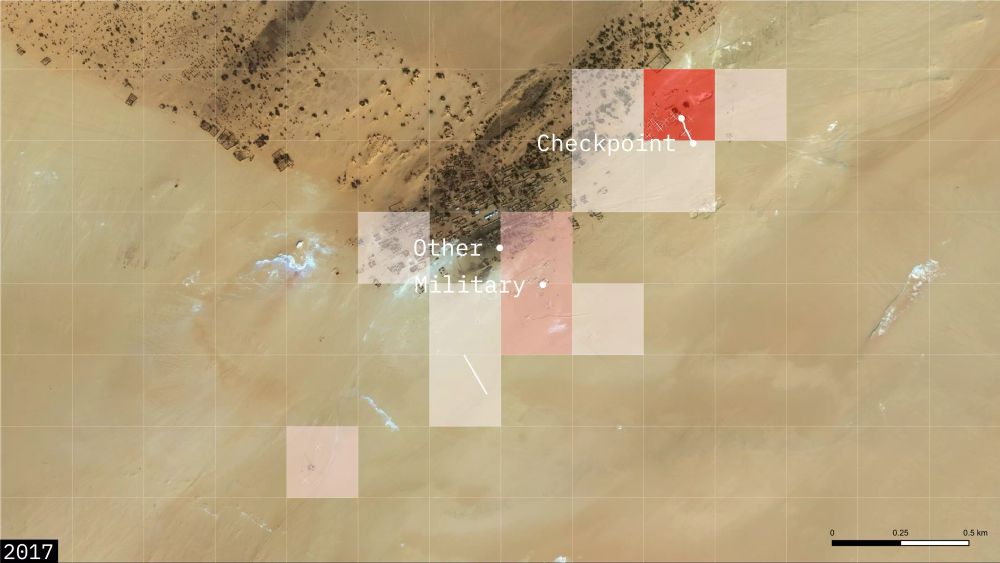

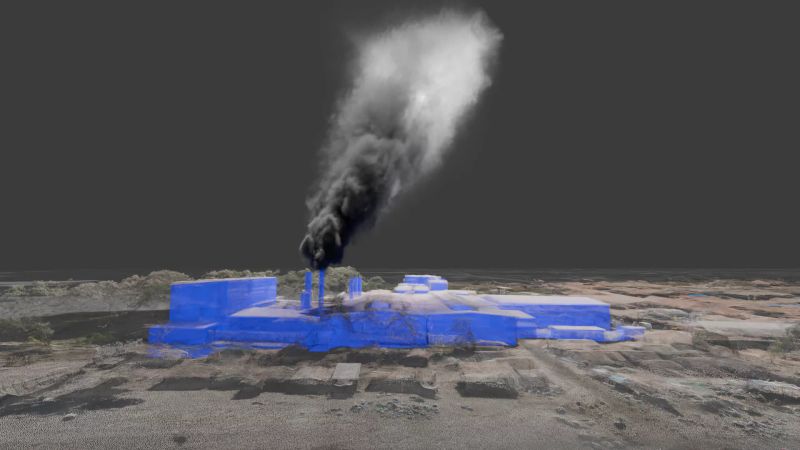

Border infrastructures, police checkpoints, aerial surveillance and the spatial apparatus of the hostil environment

The first border environments (the Gambian coastline and the desert border between Niger and Algeria) are located in Sub-Saharan Africa, where long-standing exchange networks and mobilities have been illegalised through European authorities’ border externalisation practices. These areas have been subjected also to what might referred to as forms of “accumulation by displacement”, i.e. intensified practices of capitalist extraction that by depleting resources and creating toxic sacrifice zones often lead, in complex and non-linear ways, to displacement.1 This first part of the project will focus on instances in which Hostile Environments emerge at the intersection of border violence and resource extraction in the context of global climate change, or, in other words, where resource frontiers encounter bordering practices.

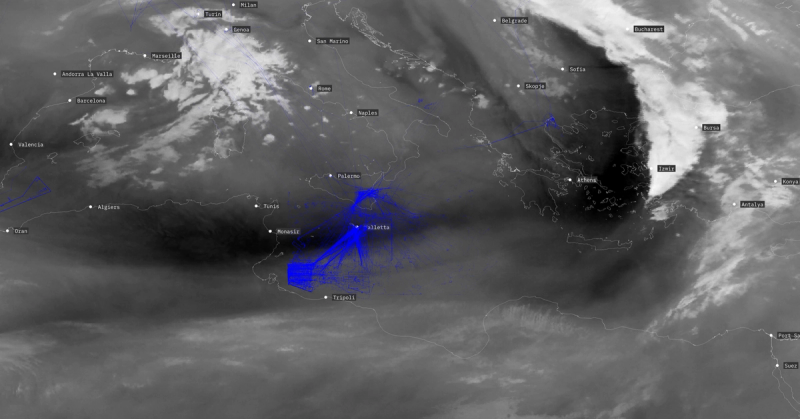

The second border environment comprises two locations where actual European borders are crossed: the Central Mediterranean and the Alps. While geographically quite distant, these sites are connected through European migration policies that lock land and sea in a continuum, as the hardening of Europe’s internal borders is triggered by the arrivals of migrants on Italian shores. Here we will pay particular attention to how the pervasiveness of border surveillance and the weaponisation of borders’ material and legal geographies create Hostile Environments. At the same time, we will also inquire into how solidarity groups attempt to open up spaces of “pirate care” against these practices.2

The last site focuses on locations where Hostile Environments function as a set of administrative practices of exclusion connected to racialised geographies of border control and policing. Here forms of “everyday bordering” make it impossible to live a normal life for those racialised as migrants, regardless of their juridical status or whether or not they have recently crossed international borders.3 In the UK, local authorities, governmental agencies and private business have increasingly been asked to share data about their users/clients with enforcement agencies, and a wide range of figures (doctors, teachers and university lecturers, but also landlords, bank employees and driving instructors) have been surreptitiously turned into border-control agents, conjuring up diffused atmospheres of surveillance. In Calais, a vast array of micro-tactics of exhaustion has been mobilised on a daily basis to deter and expel migrants: from evictions and the confiscation of tents and sleeping bags, to the harassment and criminalisation of solidarity groups that provide food, shelter and legal support.4

Altogether, the project sets out to produce new conceptual grounds for rethinking the relation between environment and migration, and to intervene in public debates on the human and environmental cost of border control.